Keep Hearing the Skies!

At New Year's Eve, as 2005 -- our planet's most recent annus horribilis -- passed into mist, we were in the bedroom, at the rear of our apartment on the third floor of an 1870s brownstone, which is tucked quietly away in the normally placid heart of a peaceful Brooklyn neighborhood. The radiators had come silently on, and it was already hot in the room. So despite the near-freezing temperature outside we opened a window and let a bit of chill in. Heard all the noises from the surrounding streets carried in on crisp air, the air of those crystalline cold nights when everything is silent until someone shouts blocks away, or a foghorn blows, or a trashcan lid closes, and you feel the sound could reverberate for infinity, ringing into the sky.

Then, at about 11:30 p.m., a low-flying plane began performing laps over our heads. Now the sound of airplanes is not in itself unusual for us. We seem to be situated in a major flight path, so that frequently we hear, descending from greater or lesser altitudes, jets making their way back to LaGuardia or JFK from points north, south, west, or east. (Impossible to tell which just from the sound, given that circling maneuver employed by pilots preparatory to landing.)

But I don't think we'd ever heard this before: a plane so low it might have been buzzing our antennae, its diesel growl traveling from one ear to the other, going silent for perhaps 30 seconds -- and then flying back towards us, thence to its 30-second oblivion on the other side. And back again. And back again. It wasn't a helicopter, which I've heard in the neighborhood twice, when the police were spotlight-sweeping the area for some fleeing suspect. This was clearly the engine of an airplane moving in a swoop. It continued for easily 45 minutes to an hour.

Someone with more knowledge of aeronautics than myself (i.e., anyone) could posit 15 reasonable explanations for what was going on up there -- why a small aircraft was flying laps at low altitude for such a length of time. But I can't think of one. Not that I've devoted this past week to pursuing an answer.

But the sound was oddly appropriate to our activity just then. As others were popping corks and waiting for balls to drop, we were watching TV -- and getting caught up, to our surprise, in a movie neither of us had seen in years: The Thing from Another World. The 1951 sci-fi thriller concerns an Army Air Force detachment sent to investigate a peculiar discovery at the military's northernmost outpost, near the North Pole. Seems the expeditionaries have found an object of almost immeasurable size lodged beneath the polar ice. Upon investigation it appears to be a spacecraft. No telling how far back it landed, or what crypto-metalloid substance it was made from, let alone the craft's point of origin. Or the identity -- if that's the word -- of the strange-looking creature seen through a transparency in the craft's outer shell, frozen within.

The craft is irrevocably damaged in the process of extricating it from its frozen coverage; but the creature is removed and preserved in its sheltering block of ice. The base personnel decide to thaw it out. The ice thaws. The thing gets loose.

The craft is irrevocably damaged in the process of extricating it from its frozen coverage; but the creature is removed and preserved in its sheltering block of ice. The base personnel decide to thaw it out. The ice thaws. The thing gets loose. We'd both witnessed the film at younger ages and remembered it as a silly, pre-fab, atomic-era creature feature about an extraterrestrial carrot. It's good to know you can actually get more open, more innocent in a way, as you get older. The Thing revealed itself at greater distance as solid B-grade horror, far better than the '50s average, and undoubtedly a classic of its modest genre. The literate, lightning-quick screenplay, by Charles Lederer and an uncredited Ben Hecht, takes off from Don A. Stuart's creepy short story "Who Goes There?" Though credits list Christian Nyby as director, it's generally assumed that the producer, Howard Hawks, had the decisive influence. (Nyby had been Hawks' editor on Red River, among others.) The film is Hawksian in many respects -- the fast talk, the clean staging, the respect for professionalism in tight situations, the women wearing pants and not taking the macho stuff seriously. There's one great screaming shock, and the rest is absorbing in an efficient, low-key way. The cast is full of familiar second- and third-tier players from noir and sci-fi and exploitation genres of the '50s: Kenneth Tobey, Margaret Sheridan, Dewey Martin, John Dierkes.

The airplane, our own Brooklyn Buzzer, materialized not long after the movie started. There's a preponderance of flying scenes in the early part of the picture -- tight cockpit, jammed cargo bay, exterior shots of the craft. It was strangely appealing and even synchronous that an actual plane should come through just as we were watching planes fly on the TV, the movie soundtrack growling and huffing just like the enormous wasp over our heads.

As the narrative transpires and events get out of hand on the polar airbase, tempers rise and cross-talk multiplies. It was about here that shouts began to reach us through the window -- clusters of people gathering outside, calling to each other as midnight approached.

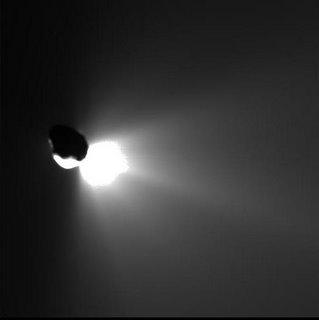

Climactically, the pilots and scientists must rig a succession of flash-fires and explosions to keep the thing at bay, and finally to kill it. Just as this began to happen, midnight chimed, and fireworks went off all around us: in the street, in the park nearby, in the yards between buildings. We couldn't see, but we could hear. Rockets flying skyward in a spritz of spark, tiny bombs whistling up and cracking open, pinpoint bursts of hot color in a vast and freezing charcoal sky.

The Thing ends with its valiant journalist character (a Hechtian tribute to his old comrades in the ink trade?) dictating his lead to the scribes back home. He ratifies the heroism of the base crew, and warns of the necessity for vigilance against those who would visit violence on us from outside. (That's "us" as in U.S. We won't go into the political implications of that in the early '50s -- or today.) The journalist concludes with words that have become de rigeur in the post-atomic age, the age of conspiracy, the watch-phrase for a generation or two of alien-huggers and hopeless plot-heads:

"Keep watching the skies!"

Or listening to them. You never know when life will imitate art, when the skies over your head will put on a radio play for your entertainment.

Here's to 2006, annus mirabilis.

<< Home